Antoine Corona

30 janvier 2025

Navicular Syndrome in Horses:

Understanding, Diagnosing and Treating

Introduction to navicular syndrome

Podotrochlear or navicular syndrome is one of the most common causes of chronic foot lameness.

Like all syndromes, it is a disease that can be identified by a set of clinical signs that are entirely characteristic, but which may have different origins.

The term ‘podotroclear syndrome’ is used to describe disorders of the podotrochlear system.

The podotrochlear system is made up of several very distinct anatomical structures.

Anatomy of the podotrochlear apparatus

To fully understand podotrochlear syndrome, a basic understanding of anatomy is required.

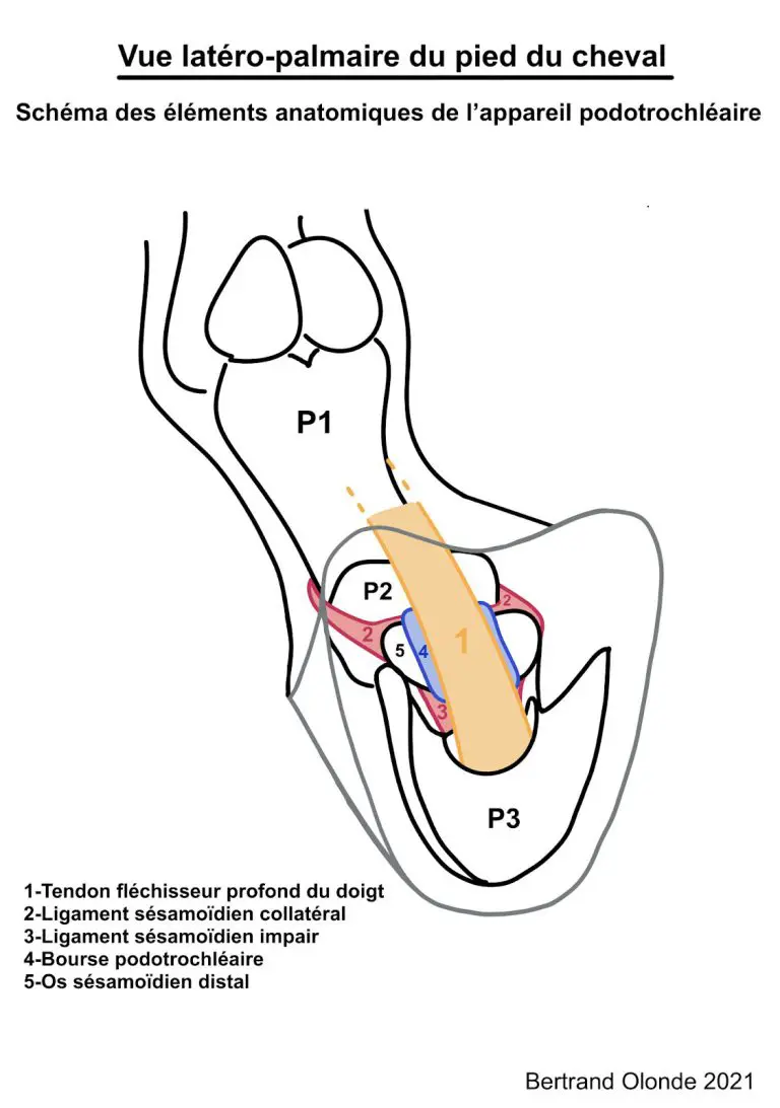

The diagram below (figure 1) shows the main anatomical structures that make up the horse’s podotrochlear apparatus.

The podotrochlear apparatus is made up of :

-

bone: the distal sesamoid bone, otherwise known as the navicular bone

-

1 tendon: the deep flexor tendon of the finger

-

several ligaments: the collateral sesamoid ligament, the odd ligament, and if we want to be perfectly exhaustive, we could even mention the chondro-sesamoid ligaments.

-

1 synovial structure: the podotrochlear bursa, which acts as a ‘slide’ for the tendon on the navicular bone.

Figure 1: Lateral-palmar view of the podotrochlear apparatus

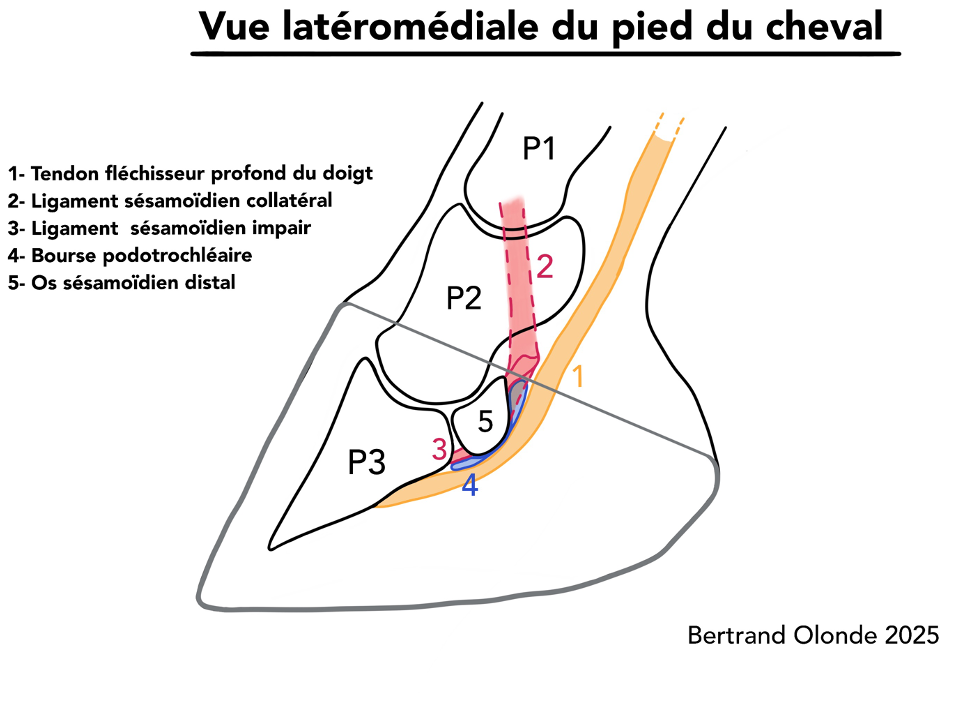

Figure 2: Lateral-medial view of the podotrochlear apparatus

When you consider the anatomy of this region of the foot, it’s easy to see how talking about podotrochlear or navicular syndrome can imply the appearance of lesions of a totally different nature and location.

As a result, management and prognosis will have to be adapted on a case-by-case basis.

In a way, there is a ‘navicular horse’ and a ‘navicular horse’.

What is the purpose of the podotrochlear device?

The lateromedial view (Figure 2) clearly shows an inflection of the deep flexor tendon of the finger when it is in contact with the navicular bone.

The physiological tension of the tendon and its change in direction create pressure on the navicular bone.

Consequently, during movement, the deep flexor tendon must be able to slide over the tendinous surface of the navicular bone, also known as the facies flexoria.

The facies flexoria, covered in fibrocartilage, and the podotrochlear bursa, the synovial cavity between the navicular bone and the tendon, are essential to ensure that the tendon slides over the distal scutum represented by the navicular bone.

Figure 3: During weight-bearing, flexion of the distal interphalangeal joint (between P2 and P3) relaxes the sesamoid ligaments and the deep flexor tendon.

Conversely, when the finger is extended, these structures will be under tension and may cause pain.

Clinical signs of ‘navicular’ disorders

Static examination: visible signs

This condition mainly affects the front feet.

Firstly, the conformation of the feet and their plumbness give a certain amount of information.

Some horses with long feet and crushed heels are more likely to present pain in the rear part of the foot and, why not, in the podotrochlear apparatus.

All the more so if the natural plumb is rather straight-pointed.

On this point, we must be careful not to confuse a compensated vertical plumb line with a naturally straight plumb line.

Other observations may be of interest, such as the volume of the front feet (Figure 2).

A foot that is significantly larger than the other may indicate that weight is transferred preferentially to one of the front limbs.

This occurs when the pain is chronic.

Figure 4: The professional noted that the right foot was more developed than the narrower left foot.

Screenshot of a static software review page

Next, observing the horse’s postural behaviour is one of the best ways to gather information.

From the side (figure 3), he can relieve pain in a foreleg, the ‘navicular foot’, by positioning it in unipodal static protraction (he places the foot forward).

If both feet are affected, he will alternate this analgesic position from one foot to the other (bipodal pain).

Another clinical postural sign, less visible to the uninitiated, is that the horse may re-centre its support under its chest in order to better unload the opposite foot (figure 4).

Figure 4: Photographs of the foot. Note the forward position, i.e. protraction, of the left foreleg.

In addition, at the end of shoeing, the heels are crushed, degrading the horse’s locomotor capacity.

Photo of the anterior teeth sagittal view with ‘Duplot’ shoeing after 5 weeks

Figure 5: Photograph of the foot. Note the preferential support of the right forefoot under the weight.

After 1st shoeing the horse retains its initial postural appearance.

To complete our static examination, we can sometimes see synovial distension of the foot joint or swelling of the pastern hollow, common in jumping horses.

Foot probing or a ‘plank test’ can also give relevant information about the health of the podotrochlear apparatus.

Note: In the stall, the horse can sometimes be positioned underneath itself by heaping straw under its heels in order to relieve the navicular region and artificially raise its heels momentarily.

Dynamic examination: observing movement

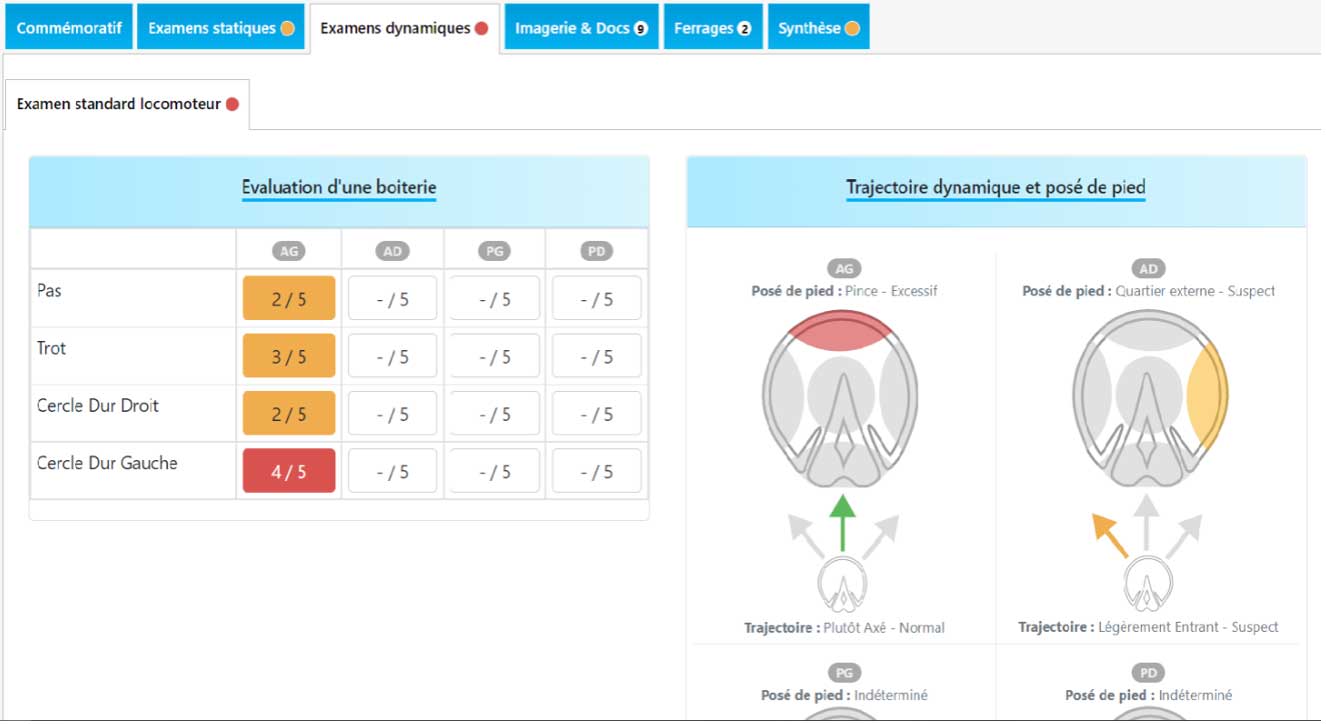

It is during this phase of the examination that the practitioner objectifies any lameness and gives it a grade (see the article How to detect lameness).

However, observing the horse in movement can go further.

A certain way in which the horse moves may be more or less suggestive of navicular syndrome.

In fact, most people suffering from navicular syndrome will have a strong tendency to load the claw of the foot to relieve pressure on the rear part of the foot, which includes the podotrochlear apparatus.

More concretely, the area of impact of the foot at the moment of landing is the toe (Figure 5).

We also pay attention to the landing of the healthy limb, because the horse can modify the impact zone of the non-painful foot and its trajectory.

This is quite logical: the horse shifts its weight and therefore its centre of gravity towards the healthy limb so that its movements are less painful.

Figure 6: The affected limb is the left foreleg, with a pincer impact zone on the ground.

It can be seen that the right foreleg tends to land in an external quarter, as a result of the centre of gravity moving towards the healthy limb and a retracting trajectory that allows the horse to load the non-painful limb.

Screenshot of an orthopaedic report generated by HIPPOTYPOSE.

The ‘navicular’ horse often has reduced gaits. Certain conditions allow the practitioner to refine his observations.

One example is the amplification of lameness on hard ground or in the circle.

Information can also be gathered by examining the horse at work or in competition.

In show jumping, for example, a ‘navicular’ horse may prefer to land on one foot or lose its trajectory.

Diagnosis of navicular syndrome

Imaging techniques used

To confirm the diagnosis of navicular disease, it is clear that imaging techniques must be used.

An X-ray examination is essential in the first instance. However, radiography has its limitations.

It cannot assess all the tissues of the foot.

We therefore opt to supplement imaging with an ultrasound scan, or even an MRI.

MRI is the examination of choice, providing a maximum amount of information.

Limitations and necessary additions

Although modern imaging techniques are highly effective in revealing lesions, a diagnosis cannot be made on the basis of images alone.

Lesions do not always mean pain. Some lesions are well tolerated. Some are degenerative and can appear with age without much impact either. Others may have had an impact on locomotion, but are no longer active at the time of the examination.

It is therefore important to understand that complementary examinations are indicated to confirm diagnostic hypotheses that originate from the clinical examination (observation, palpation, tests, flexions, etc.).

The origin of the pain must be determined as precisely as possible by the clinical examination, which may include diagnostic anaesthesia. It is only once the origin of the lameness has been established that X-ray or MRI images can be interpreted.

Management of navicular syndrome

Over the last twenty years, the quality of diagnosis and treatment has greatly improved.

Firstly, advances in imaging techniques have made it possible to describe lesions much more accurately.

Secondly, farriery has evolved enormously to offer suitable orthopaedic fittings.

And above all, for some time now, we’ve been focusing on prevention.

All these factors have contributed to a change in the way we approach the diagnosis of navicular disease.

With proper management, a horse suffering from podotrochlear, or navicular, syndrome can continue to participate in sport, sometimes even at a high level.

In the acute phase, rest may be recommended to reduce inflammation as much as possible, or the horse’s working conditions may be adapted.

Veterinary approach: treatment and follow-up

The veterinary surgeon’s therapeutic arsenal is varied. The first step is to treat the pain and reduce the inflammation.

General anti-inflammatories are often used, at least in the acute phase.

Subsequently, depending on the nature of the lesion and the progress of the lameness, the vet may recommend infiltration, or even surgery in some cases.

Long-term management of these cases invariably involves the skills of the farrier, whose orthopaedic approach is always a fundamental pillar of the therapeutic strategy.

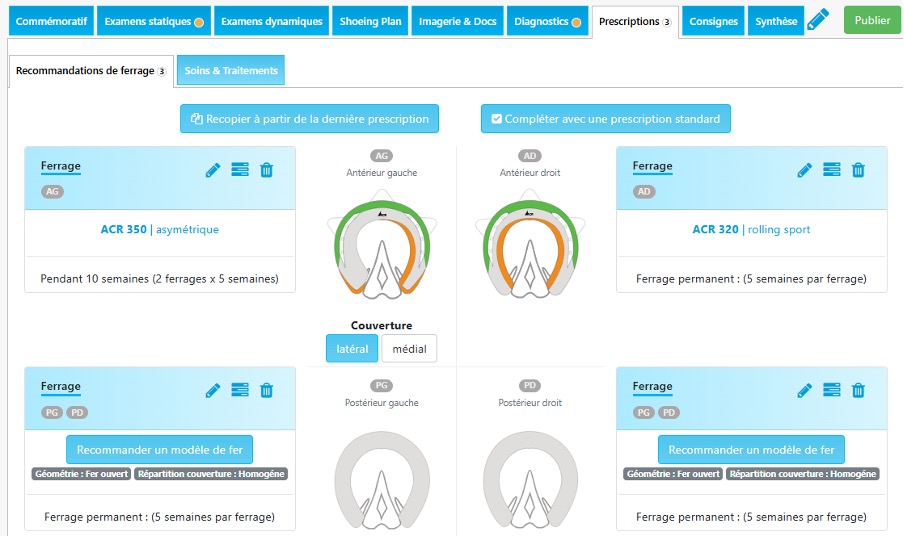

The role of therapeutic farriery :

This begins with an analysis of the horse’s anatomical characteristics (its balance, the conformation of its feet, etc.), which is compared with the nature of the injury causing the problem.

This analysis, which is usually the result of discussions between the vet and the farrier, enables the horse’s biomechanical needs to be defined.

Trimming allows the phalangeal angles to be corrected and the horse’s comfort zone to be found, in its natural plumb.

As far as the type of shoeing is concerned, we prefer light shoeing to achieve the desired biomechanical effect, taking into account the horse’s lifestyle, discipline, etc.

In general, farriers have 3 levels of action to treat podotrochlear syndrome:

- Level 1: Onion shoes will protect and limit heel digging into soft ground.

- Level 2: Egg bar shoes are very often proposed for sport horses, but will quickly find their limits in certain uses. Napoleon shoes are also often used during the acute phase.

- Level 3: compensated Egg bar shoes, used in rather severe chronic cases.

There are still other alternatives, such as the rocking shoe (a compensated shoe with a break-over point set far back), which is effective in reducing stress on the podotrochlear apparatus, or the H-shoe, which encourages the foot to start.

This ‘therapeutic’ farriery must be accompanied by regular veterinary monitoring.

And if progress is to be made, the owner must agree to have his horse’s shoes checked every 5 weeks.

After this period, the balance of the foot will often be compromised and the benefits of shoeing will be reduced.

Recommended resources and tools

HIPPOTYPOSE: Orthopaedic monitoring platform for horses